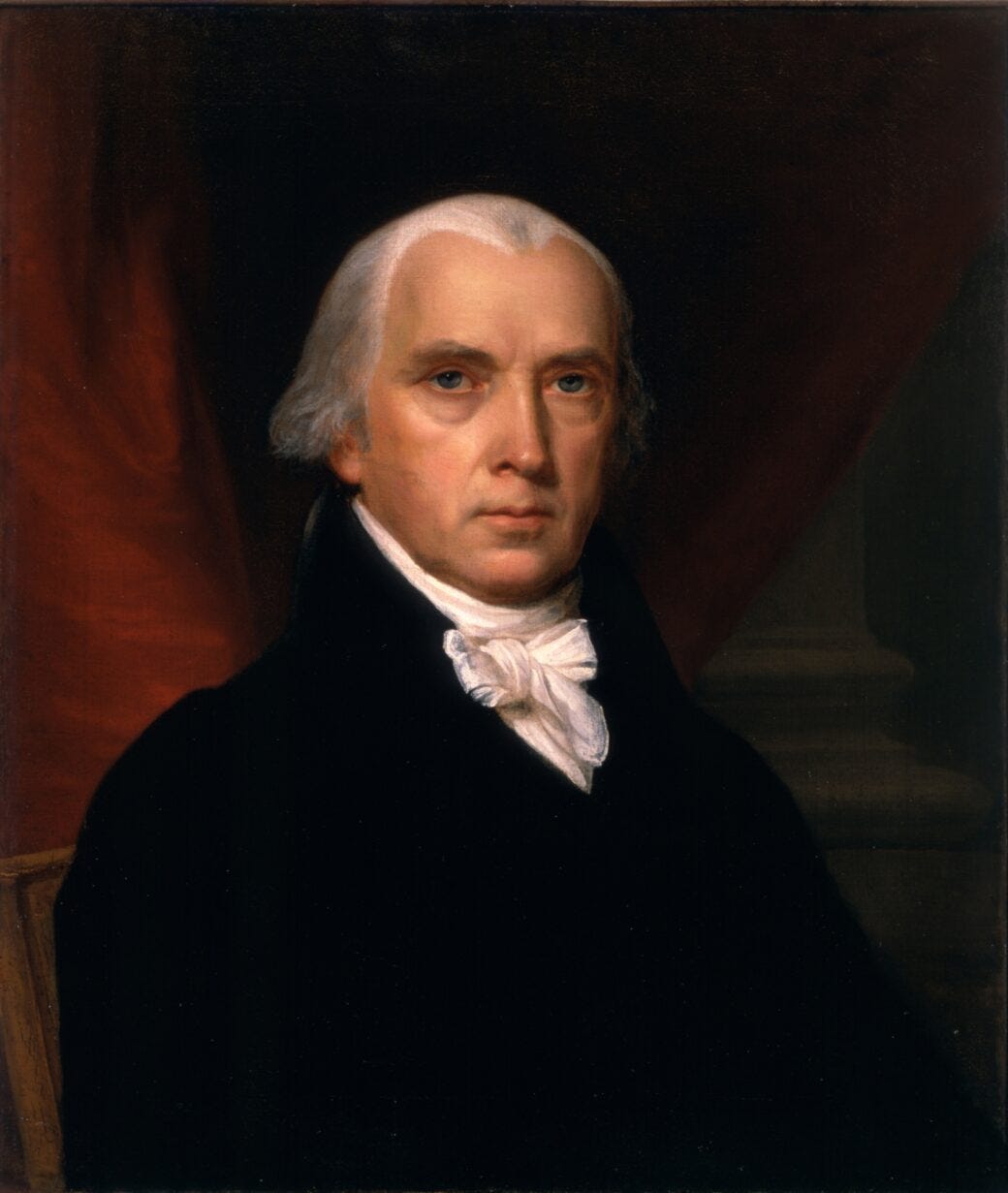

James Madison:

Navigating Crises with Principle and Patience

James Madison, the fourth President of the United States, led the nation through a period of intense internal and external pressure. His presidency (1809–1817) was defined by the War of 1812, trade conflicts, and deep regional divisions — challenges that offer enduring lessons for today.

Arriving at Difficult Decisions

One of Madison’s defining moments was the decision to declare war on Britain in 1812. The path to that choice was neither simple nor immediate. Britain’s interference with U.S. trade, impressment of American sailors, and support for Native American resistance threatened national sovereignty. Madison and his advisors weighed these threats against the potential costs of war, the readiness of the military, and the fractured public opinion at home.

He relied heavily on principled deliberation: examining the long-term implications of action versus inaction, consulting with Congress, and carefully assessing both immediate and future risks. His patience allowed time for gathering intelligence, evaluating military readiness, and gauging political support — though it also drew criticism from those urging faster action.

Checks, Balances, and Internal Friction

Madison’s system of checks and balances both constrained and strengthened his presidency. Congress had the authority to declare war, control funding, and oppose policy. Regional factions — New England states opposed the war while Southern and Western regions pushed for it — applied additional pressure. Early economic disruption and military unpreparedness intensified criticism.

These checks slowed Madison’s decisions, but they also forced careful deliberation, coalition-building, and a broader assessment of consequences. In the end, the constraints of constitutional process strengthened the legitimacy and endurance of the outcomes. The War of 1812 was risky, but the deliberate, measured approach helped ensure that victory, when it came, had firm legal and moral grounding.

Lessons for Today

Modern parallels are striking. Today, leaders face complex foreign pressures, internal divisions, and the tension between urgent action and long-term outcomes. Madison’s approach illustrates that:

Principled patience matters — acting too quickly can exacerbate crises.

Constraints are not merely obstacles — they force rigor, deliberation, and coalition-building.

Long-term outcomes require layered thinking — short-term discomfort is often necessary for enduring stability.

History shows that effective leadership is rarely immediate or spectacular. Madison’s presidency reminds us that navigating crises with care, respect for process, and adherence to principle builds resilience and legitimacy that endures far beyond the immediate moment.

When faced with pressure from multiple directions, how can we ensure that our actions serve long-term stability rather than short-term gain? How might patience, deliberation, and respect for process strengthen the outcomes we seek, even when the results are not immediately visible?